Mothers’ pay lags far behind men

Women who return to work after having a baby fall even further behind men in earning power, a report by the Institute for Fiscal Studies has said.

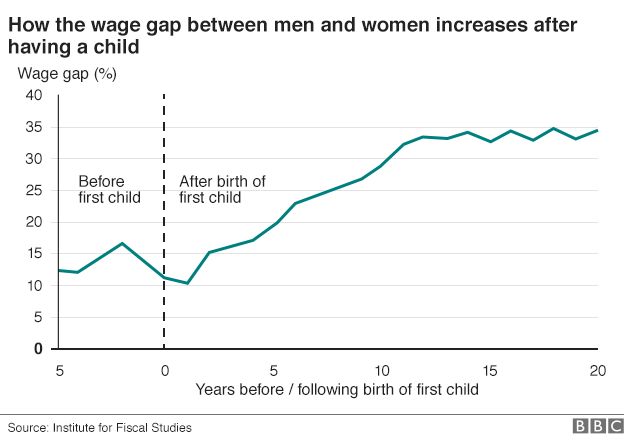

The gap between hourly earnings of the two sexes becomes steadily wider after women become mothers, the IFS says.

Over the subsequent 12 years, women’s hourly pay rate falls 33% behind men’s.

The IFS says this is partly because women who return to work often do so in a part-time capacity and miss out on opportunities for promotion.

Robert Joyce, one of the IFS report’s authors, said women who chose to cut their hours on returning to work were not penalised with an immediate cut in their hourly wages.

However, he said: “Rather, women who work half-time lose out on subsequent wage progression, meaning that the hourly wages of men (and of women in full-time work) pull further and further ahead.”

Six ways to tackle the gender pay gap

TUC general secretary Frances O’Grady said: “It is scandalous that millions of women still suffer a motherhood pay penalty.

“Many are forced to leave better-paid jobs due to the pressure of caring responsibilities and the lack of flexible working.”

The Mum tax? Four women’s experience

- Alison Davies, 40, returned to work part-time to her job with the police after her having first child 11 years ago: “Due to the nature of my job I was demoted. I could not see the point of paying for a childminder and spending time away from my baby to open post and make tea for the people I used to manage so after six months I quit. I have started my own small business home boarding dogs but I feel my degree in biological science and post grad diploma have been wasted.”

- Nerys Dodds, who works in IT support at a college in Norfolk: “I must be one of the unmentioned luckier ones. Since returning to work three years ago from maternity leave I have been encouraged to progress to higher managerial roles and been allowed to change my working hours and contract a total of three times to allow a slow increase in hours as my children grow.”

- Agi Turowska, a project coordinator from London, returned to work just over a year ago to a “changed job” after her company was restructured. She said: “None of the changes include a pay review. I was told there were a lot of uncertainties and redundancies followed, which naturally made me worried I may lose my job if I object to taking on more.”

- Kate from Oxford, whose full name we have not used at her request: “I decided to return to my job on an 80% contract, to manage childcare. Since my return, I’ve had almost all of my responsibilities and projects stripped from me and I’ve been left with the more basic, routine jobs. As my performance in the company’s annual review and promotion system relies on me working on high profile projects I’m now set to perform badly in this year’s review which will affect my bonus and pay rise next year.”

Men are 40% more likely than women to be promoted into management roles, separate research by the Chartered Management Institute and XpertHR found.

It said this difference in promotion rates was one of the main causes of the gender pay gap.

Mark Crail, content director at XpertHR, said: “The gender pay gap is not primarily about men and women being paid differently for doing the same job.

“It’s much more about men being present in greater numbers than women the higher up the organisation you go. Our research shows that this gap begins to open up at relatively junior levels and widens – primarily because men are more likely to be promoted.”

On average, women earn 18% less per hour than men, according to the IFS research.

However, this gap between men’s and women’s hourly pay rates has been closing in recent decades – it was 23% in 2003 and 28% in 1993.

But after women return to work following the birth of a first child, that wage difference per hour widens steadily.

The Fawcett Society, which campaigns for equality, said more quality part-time jobs were needed to address the pay gap.

Sam Smethers, Fawcett’s chief executive, said: “Part-time workers can be the most productive, yet reduced hours working becomes a career cul-de-sac for women from which they can’t recover.”

Once children are born, many women return to work only part-time or stop working altogether.

The IFS found that in the 20 years following the arrival of a first child, the average woman had worked for four years fewer than men.

And men had spent nine years more than women working for 20 hours a week or more.

“Comparing women who had the same hourly wage before leaving paid work, wages when they return are on average 2% lower for each year spent out of paid work in the interim,” the IFS found.

“This apparent wage penalty for taking time out of paid work is greater for more highly educated women, at 4% for each year out of paid work.

“The lowest-educated women (who actually take more time out of paid work after childbirth) do not seem to pay this particular penalty, probably because they have less wage progression to miss out on,” the IFS explained.

Labour’s shadow women and equalities minister Angela Rayner said the report highlighted an unacceptable wage gap.

“There is little incentive for those young women who have just qualified with their A-levels and are considering university, to see that in the future they will still be paid less than the men they study alongside.

“The report also shows that having a child costs women both in their pay packet and in their chances of being promoted. Mothers should not be penalised for having a family.”

Earlier this year the government announced plans, to start in 2017, under which 8,000 employers with more than 250 staff will have to reveal the number of men and women in each pay range, and show where the pay gaps are at their widest.

A government spokeswoman said: “The gender pay gap is the lowest on record but we know we need to make more progress and faster.”

“That’s why we are pushing ahead with plans to force businesses to publish their gender pay and gender bonus gap – shining a light on the barriers preventing women from reaching the top.”

[Source: BBC]