Formal badge for non-formal skill

Across construction sites dotting five states — Haryana, Telangana, Odisha, Chhattisgarh and Delhi — a novel scheme is underway to certify the skills acquired by workers in the unorganised sectors through traditional, non-formal learning channels.

Depending on the progress of the Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL) scheme, which has been kicked-off with a focus on construction sites employing more that 200 workers across these five states, the Ministry of Labour & Employment and the Ministry of Skill Development are hoping to expand the programme to other states and enlarge its scope to include sectors other than construction.

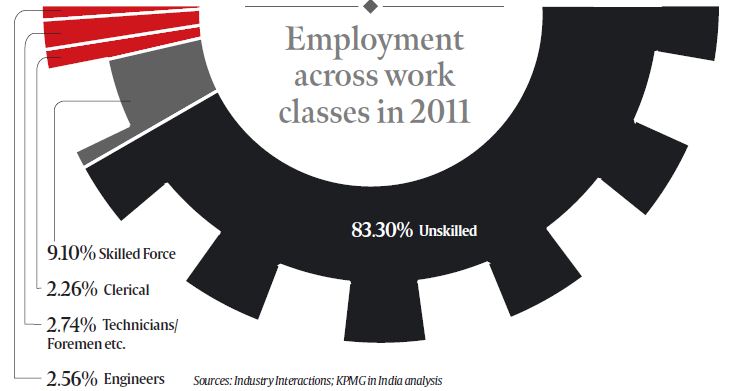

The project may be of particular relevance to a country where just 2 per cent of the workforce is certified as skilled, as against skilled workforce levels of 96 per cent in South Korea, 80 per cent in Japan, 75 per cent in Germany and 70 per cent in Britain. The poor skill level among India’s workforce is attributed to the dearth of formal vocational educational framework and lack of industry-ready skills. Most deemed to be outside the skilled category in India are those who have typically picked up a skill while on the job, without any formal degree to back this up.

The project may be of particular relevance to a country where just 2 per cent of the workforce is certified as skilled, as against skilled workforce levels of 96 per cent in South Korea, 80 per cent in Japan, 75 per cent in Germany and 70 per cent in Britain. The poor skill level among India’s workforce is attributed to the dearth of formal vocational educational framework and lack of industry-ready skills. Most deemed to be outside the skilled category in India are those who have typically picked up a skill while on the job, without any formal degree to back this up.

Two stand-out things about the scheme are the attempt to involve the industry in firming up the checklist of competencies for various trades and trying to standardise skill levels across a particular sector by empanelling independent trainers for the skill assessment and training. “While the official estimate of the percentage of skilled workers in the overall workforce is around 2 per cent, there are lakhs of people who are illiterate or semi-literate but are adept the art of craftsmanship or skilling for generations. Varanasi or Kancheepuram weavers, gold and jewellery workers of Jaipur, diamond workers of Surat and many more. These people are skilled and working, they need to be certified. The (RPL) programme is an attempt to bring them formally to the skilling list, starting with the construction sector,” a senior skill development ministry official said.

A labour ministry official involved in the first leg of the programme said that progress of the RPL scheme in the five states of Haryana, Telangana, Delhi, Odisha and Chhattisgarh has been “particularly encouraging”. He said that while the scheme was open to all the states, the five were among the first lot to show interest in the implementation of the scheme and hence included in the first phase. The evaluation of skills and training is extended by selected training providers who have been empanelled for the job, with sector-wise specialisation.

A labour ministry official involved in the first leg of the programme said that progress of the RPL scheme in the five states of Haryana, Telangana, Delhi, Odisha and Chhattisgarh has been “particularly encouraging”. He said that while the scheme was open to all the states, the five were among the first lot to show interest in the implementation of the scheme and hence included in the first phase. The evaluation of skills and training is extended by selected training providers who have been empanelled for the job, with sector-wise specialisation.

Officials said the selection of site and for pre-assessing the workers selected for imparting training under the scheme is currently restricted to construction sites having more than 200 construction workers. Importantly, the workers are pre-assessed on the competencies mentioned in the checklist for various trades prepared in consultation with the construction industry.

The training providers being roped in for the scheme, who can be either private sector players or government entities, are being entrusted with the task of charting out the methodology to certify the candidates in both theory and practical training sessions, getting government bodies or industry group’s approval in the vocational skill training and tying-up with corporates to utilise work-site for training. Under RPL, a target to certify an estimated 10 lakh workers has been set, officials indicated.

The country has had numerous mechanisms for vocational education and training, spearheaded by over at least a dozen central ministries and several regulators such as AICTE, UGC and technical education boards. In the private sector, employers such as Infosys and Maruti Suzuki have set up in-house facilities for skilling fresh graduates to meet their own requirements while a number of private players such as the Tata Group and public sector utilities including NTPC Ltd have adopted ITIs to get trained entry-level personnel.

The country has had numerous mechanisms for vocational education and training, spearheaded by over at least a dozen central ministries and several regulators such as AICTE, UGC and technical education boards. In the private sector, employers such as Infosys and Maruti Suzuki have set up in-house facilities for skilling fresh graduates to meet their own requirements while a number of private players such as the Tata Group and public sector utilities including NTPC Ltd have adopted ITIs to get trained entry-level personnel.

For a majority of those who are outside the ambit of these formal training plans, access to vocational skills is generally through the informal route, a problem that is further compounded by the fact that most vocational training and education systems continue to remain either unconnected with the needs of the industry.

The biggest problem, experts point out, is that there are no common yardsticks for measuring work-related competencies across various mechanisms of learning skills.

The biggest problem, experts point out, is that there are no common yardsticks for measuring work-related competencies across various mechanisms of learning skills.

In fact, the groundwork to create common standards incorporating the industries-level requirements for different kinds of job roles, and aligning the vocational training schemes with these standards was initiated by the previous UPA government, which had notified the National Skills Qualifications Framework (NSQF) in December 2013. It was designed to enable the learner to acquire skills required by the National Occupational Standards (NOS) to be able to perform a particular job role and organised them as a series of qualifications across 10 levels-from level 1 to 10.

The NSQF mandates that by December 2016, only NSQF-compliant courses would be eligible for government funding. The Minister for Skills Development and Entrepreneurship under the NDA government has taken this forward, with the announcement that the recruitment rules for the central government and PSUs will be amended by December 2016 to define eligibility criteria for all positions, as mandated in NSQF. Alongside, state governments and state sector PSUs are also likely to be asked to amend their recruitment rules.

For the 700 million-strong workforce that India will have by 2020, the prospect of a demographic dividend hinges heavily on the country’s ability to empower the workers with the right skills.

For the 700 million-strong workforce that India will have by 2020, the prospect of a demographic dividend hinges heavily on the country’s ability to empower the workers with the right skills.

Global experience

The expectations-delivery mismatch that leads to drop-out is not unique to India’s vocational education system. Many developed and emerging economies have faced similar challenges and have deployed innovative strategies to overcome them, according to global consulting firm Accenture’s report on ‘Overcoming India’s skills challenge:

Germany

Its much acclaimed Dual Vocational Training System ensures there is a job ready for every trainee enrolled in vocational school. After students complete their mandatory years of schooling (usually around age 18), they apply to a private company for a two- or three-year training contract. If they are accepted, the government supplements trainees’ on-the-job learning with broadbased education in their field of choice at a publicly funded vocational school. This helps to set trainees’ expectations about the type of job they will get, right from the first day of the training. Trainees who pass the course examination also receive a certificate that enables them to transfer to similarly oriented businesses if they decide not to continue with the initial employer contract.

Australia

Australia

An apprenticeship system forms the backbone of the country’s technical and trades skilling effort. But the system faced several problems, including low completion rates, inconsistent training quality, poor wages for apprentices and a lack of mentoring support. In its 2011-2012 budget, the Australian government decided to earmark A$101 million for mentoring. The funds support mentoring assistance for up to 40,000 eligible Australian apprentices, over four years, in the traditional trades as well as in small- to medium-size businesses. Mentors will be experienced tradespersons and will help apprentices learn to manage difficult situations (such as living away from home) and complete their training.

China

The country’s position as a global leader in manufacturing is ably supported by its vocational and technical education system. Enrollment in secondary vocational education totals about 22 million, more than half of high school enrollment — the highest proportion in any country in the world. China has worked to ensure that teachers in vocational schools stay current with the requirements of modern industry. For example, such teachers are required to spend one month working in industry each year, or two months every two years. In addition, many schools employ a significant number of part-time teachers who also work in industry.

[“source – indianexpress.com”]