Pyrex: Fire and Pride Are Glassware’s Heart and Soul

Get to work in your kitchen, and chances are at one point you’ll need Pyrex. Not just any oven-safe glass dish, but a Pyrex — a name synonymous with baking. One of the few brands to reach iconic status in the American kitchen, Pyrex has become the symbol of a cooking need met with a practical solution, which accounts for the 40 million products sold annually.

The brand has been a part of American homes for 100 years, since, as legend has it, Bessie Littleton asked her husband to bring home a replacement for her broken casserole dish. Luckily for Bessie, her husband was Corning (GLW) glass scientist Dr. Jesse T. Littleton, who had access to extremely strong glass materials. To please his wife, Dr. Littleton sawed off the bottom of a battery jar — a glass container similar to a canning jar that contained ingredients for battery power — and the first Pyrex product was made. The accidental invention inspired Corning to launch a bakeware line called Pyrex in 1915.

Today, Pyrex is produced at a 22-acre plant in Charleroi, Pennsylvania. At different times throughout the company’s history, Pyrex made tableware and cups for Hilton (HLT) hotels, plate gifts for bank giveaways and intricately painted glass coffee carafes among other collectibles.

In total, 80 million of the nearly 120 million American households contain a Pyrex product, making Pyrex the cornerstone brand of owner World Kitchen’s portfolio. Other World Kitchen products include Corelle, CorningWare, Chicago Cutlery and Baker’s Secret, which are primarily produced outside of the U.S.

Along the Monongahela River, the quiet town of Charleroi watches over the 100-year-old Pyrex plant from the hillside. In what used to be a booming industrial area sustained by steel mills and coal mines, Pyrex has now become the No. 2 employer in the town of 4,000, second only to the local hospital system. The plant is open 24 hours a day, pushing out the glass products we’ve all come to rely upon.

Chapter 1: The Fire Within

A mountain of crystal blue shards from cracked bowls and measuring cups shines against a concrete barrier. The energy taken to break the glass — a two-second fall off a conveyor belt, a slip of the hands — is no match for the raw power needed to melt the pieces to create a new product.

The broken glass graveyard at Pyrex reflects an industrial work ethic — a little rough around the edges, but glistening with potential. The glass is solid and strong, and clear and pure through and through. With a little work, the discarded pieces will be reborn.

Like the pile of cracked glass, not all manufacturing stories are pretty. They are filled with challenges and triumphs, ups and downs throughout the factory’s lifecycle, but at the heart, the truly successful products stand the test of time.

Built in 1893 as Macbeth Glass, the Charleroi glass plant merged with Thomas Evans in 1895 to become the Macbeth-Evans Glass. Corning purchased the plant in 1936, with World Kitchen taking over in 1998.

Over 300 people earn their living at the plant, most originally from the Mon Valley. Almost every employee you encounter says “welcome to the home of Pyrex” and identifies the word Pyrex with “pride.”

Mike Pascanik, 60, is a hockey official in the evenings and an equipment engineer during the day. He may meet the retirement age requirement, which would allow him to lace up his skates on a daily basis, but even after calling Pyrex home for over 38 years, he’s not done yet. “I’ll work here as long as I’m having fun,” he said.

Marty Pappasergi, a 37-year veteran of Pyrex, oversees one of the first and most important processes: batching. Batching weighs the right amounts of raw materials, also known as cullet, for each product. A scale fills, with a digital weight machine beside it. Mix is introduced into the hopper, reaches its set point and settles before moving on to the melting process. Pappasergi watches the numbers intently. He may look casual in his Pittsburgh Pirates baseball cap, but realizes the seriousness of his position. “It’s like making a cake,” Pappasergi said. “If you don’t prepare the mix properly, the cake won’t rise. If you mess up here, the quality of the product decreases.”

After batching, the mix is transported by handling and rides an elevator to another building housing the melting facility. You have to duck under conveyor belts and low hanging pipes, following a narrow path, to get through to the blazing manufacturing process. Within the cold, gray nest of machinery lays the beating heart of the Pyrex plant, what employees fondly refer to as “the tank.” The tank holds up to 200 tons of molten glass, sent out to four arteries or product lines.

The tank begins the transformation process, liquefying cullet at up to 2,000 degrees Celsius. The tank takes up to a week to heat and for that reason operates 24 hours a day, seven days a week, with employees continuously monitoring temperatures at its core.

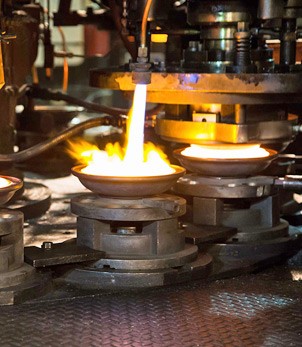

The tank drops a “glob” of intensely hot, glowing melted glass, down a chute or product line. The glob then lands in a rotating circle of molds. From there, a jet of targeted flames blast to melt and press the glass into a mold shape. A hose descends to suck up the molded piece, still over 1,000 degrees hot, and places it onto a fire polisher, blasting spouts of heat to smooth rough edges. The open flames burn bright and hot, causing the eyes to squint and water. Goggles are a necessity.

Fire is the heart and soul of Pyrex, similar to the oven creating sustenance in a kitchen, turning a wet, floppy brownie mix into a firm, pliable treat. Because the bakeware is born into such intense conditions of 1000 degrees and more, it can do the simple job of letting the food cook evenly while withstanding much lower oven temperatures.

The heat tempering process is what makes Pyrex so durable, and why its glassware has sustained over 100 years of use. The testing of bakeware at extremely high temperatures prepares it for dependable use in the kitchen at a lower energy level.

With all of the flames creating hardy products, it is only fitting that over a dozen firefighters work here — including Bill Castner Jr., the union safety coordinator who moonlights as a fire chief in North Charleroi. Castner, 33, who went to college to become a meteorologist, found it difficult to find employment in his industry and instead followed his father to the Pyrex plant. He took on the newly created position of union safety coordinator three years ago to utilize his skills as an EMT and firefighter.

“It’s very gratifying — getting everyone to and from work with ten fingers and toes,” Castner said. Because of Pyrex’s safety record inside the plant, they are able to produce up to 52 million sturdy pieces a year — almost 22 lasagna pans a minute.

Chapter 2: 100 Years of Pride

Over time, the culture of cooking evolves. Microwaves heat meals in minutes, rather than hours in a conventional oven. Instant mashed potatoes find their way to the table without any need for peeling and boiling. Families also have less time to prepare and cook daily dinners, and a one-pan feast can be a huge time-saver. Yet Pyrex products remain mostly the same.

In 1915, the first pie plate came off of the Pyrex line. The plate remains largely unchanged, with the same rippled edge. It cooks with the same even heating method, although instead of a pie, the plate may now take on a warm nacho or spinach dip. The first measuring cup debuted in 1925, and with only one adjustment from two spouts to one, it’s wrapped with the same classic red measuring lines. It is one of the most popular products in Australia — where measuring cups are known as “jugs.”

This year Pyrex will celebrate its 100th anniversary. Even with millions of rarely changed pieces sold in 50 countries, the company continues to focus on innovation.

“The greatest challenge that we’ve had at Pyrex is frankly meeting the demand the consumers have put on this brand,” said Kris Malkoski, president of North America for World Kitchen. “Our business has grown exponentially over the past few years. I think it is driven by the fact that we are really listening to what consumers want as well as looking at what’s worked in the past and bringing a steady stream of innovation to the marketplace.”

The company is celebrating its heritage by catering to enthusiasts who collect iconic pieces from the brand. Many Americans share a common memory of gathering around the dinner table to eat some kind of casserole out of a Pyrex dish. The company recognizes the tradition and remembers to respect its roots.

“When someone says they love a brand, what does that mean?” said Mike Scheffki, brand lead for Pyrex. “It goes beyond product. This is the only dish I trust to make my Thanksgiving Day meal, and when people tell you this they start welling up, because it strikes such an emotional chord with them, and you can’t help but get sucked into it.”

Charleroi employees remain fiercely loyal to the brand, proudly representing even outside the factory doors. “When we go to Walmart or Target, and it’s next to a competitor, we make sure the Pyrex is neatly stacked, make sure boxes are straight. We are never told to do that,” Castner said. “It’s just something we all picked up.”

Chapter 3: Built to Withstand Time

Like the families who embrace the Pyrex brand, so do the employees who have a hand in creating the products.

“We have many multigenerational employees here,” said John Lackovic, plant director. “Pyrex pride goes down through each generation, wanting to do it as good as or better than those before them.” You can tell that Lackovic loves his job almost as much as the baked ziti with bacon he cooks regularly in his Pyrex ware. Growing up in a restaurant family, Lackovic left the area to attend Clemson University to pursue a degree in electrical engineering. He came home to Pyrex with the hope of giving his wife and three daughters a better life.

“It’s a family-friendly environment,” he said.” “The culture and values of the company lend to the balance. One of our values is to be accountable. The job affords the opportunity for freedom outside of work when you are doing those things well.” At Pyrex, when you are doing your job correctly, the lines run smoothly, and everyone gets to go home at a decent hour to their families.

Lackovic leads the plant, but on a most humble level. He continuously refers to the Pyrex employees as a family and notes that teamwork is essential to their success. One of his mandates is overseeing quality control and improvement programs. “At the end of day when you can see them on the shelf at the store … I know the effort that took to put that glass there. It’s a very rewarding and proud feeling.”

Most manufacturers can’t seem to find a younger generation skilled enough to replace the retiring laborers. Fortunately Pyrex sees the opposite trend, with a constant influx of younger applicants.

Clint Cooper, 62, who will retire this December, oversees the apprenticeship program at the Charleroi plant. “Pyrex cannot hire enough people,” he said. The plant currently runs at maximum capacity thanks to the popular new Snapware storage product.

World Kitchen bought Snapware five years ago, bringing a big boost to the Charleroi plant. The company brought production of the glass vessels back home from China. The reshoring acquisition created a lot of growth in Charleroi and set the plant production over capacity.

For the last 30 years, Cooper has trained and supervised apprentices, many of whom have gone on to a managerial level. The apprentices are enrolled in a state-certified program that can take up to two years and up to 4,000 hours to achieve journeyman status. The program teaches students how to run and troubleshoot machines. From there ,they can go on to become a master in skills such as forming, welding and the like. “The coolest thing about this job is to pass on information,” he said. “Skill never dies.”

[source : dailyfinance.com]