The Mental Health Crisis: A Crisis Of Health, Or Education?

The epidemic of poor mental health which has swept the Western world over recent years has left no demographic untouched.

From growing antidepressant use in over-65s and suicide rates peaking in those in their late 40s to 50% of millennials reportedly having left jobs for mental health reasons and children and adolescents manifesting with symptoms increasingly early in life, no age group is immune.

Governments have tried stemming the problem through research funding, public health initiatives and education for medical professionals and yet still the statistics continue to move in the wrong direction.

But is the global mental health crisis really a health crisis, or is it a crisis of education?

What if our international grapple with mental illness has more to do with a gap in our emotional education than a gap in our health system? What if we’re parking the ambulance at the bottom of the cliff, rather than getting to the roots of the problem?

In the US, more and more schools are adding social-emotional learning to the classic curriculum of language, math, science, history and geography. In the UK, too, the Department for Education has unveiled plans to make wellbeing education universal in schools by 2020.

Knowledge is power – so arming schoolchildren with the knowledge they need to manage their wellbeing feels like an appropriate response.

But what role could universities play in rewriting adult emotional education?

University students have been one of the hardest-hit demographics when it comes to their mental health – with rates of student depression, anxiety, self-harm, eating disorders and suicidal ideation continuing to surge.

The typical age range of university students also coincides unhappily with the most common age for the emergence of mental illness, with many sufferers experiencing their first symptoms between the ages of 16 and 24.

The demand for emotional education at university

At Fika, we recently conducted some research to assess the demand for emotional education from university students, as well as graduate employers.

The findings were starker than we could have expected.

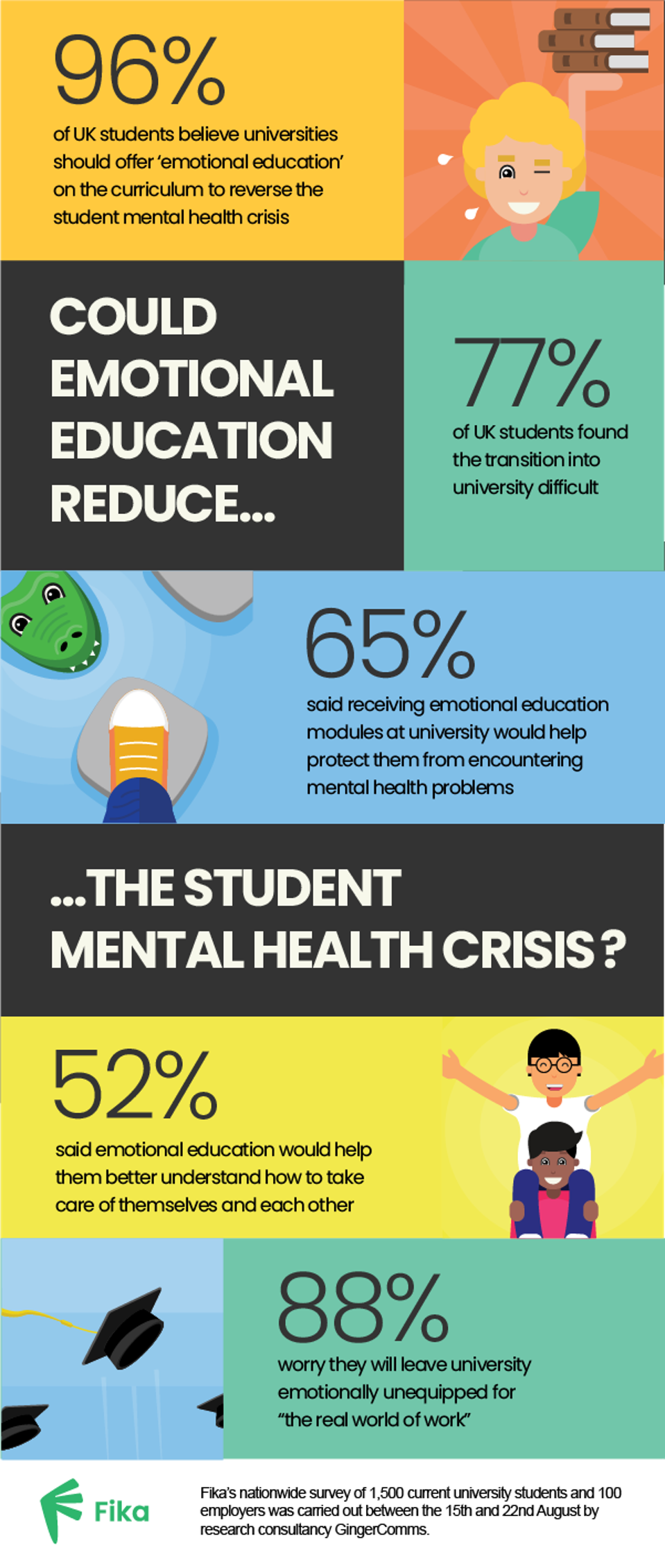

97% of UK students felt they would benefit from such modules, 96% said emotional education could help reverse the student mental health crisis, 65% said it would protect them from encountering mental illness and 52% agreed it would help them better understand how to take care of themselves and each other.

Of the employers we surveyed, a staggering 99% said offering students an emotional and social education on the university curriculum would vastly improve their chances of career success. 95% said they would like to see young people arriving in the workforce with better emotional and social skills and 87% felt graduates often lack the emotional skills they need to thrive at work.

Could emotional education reduce the student mental health crisis?

FIKA

Would emotional education improve students’ chances of employment?

FIKA

Out of a list of 19 possible attributes a graduate employee could bring to the workforce, employers ranked academic results bottom; valuing communication skills, teamwork, self-motivation and problem-solving above all else.

In the UK, university counselling services are struggling to cope with students’ growing demand for support.

And yet the thought of ‘emotional education’ at university still seems novel

Perhaps universities, famed for their academic rigour, pursuit of intellectual growth and reputations for groundbreaking research, worry that the addition of ‘emotional education’ to their offering will somehow dampen their perceived value.

But let me present you with an argument in favour of the so-called “softer” pursuit of emotional self-development in higher education.

The case for emotional education at university

The purpose of a university, according to Pearson, is to be “the guardian of reason, inquiry and philosophical openness”, as well as the enabler of “social mobility – allowing people to transform their lives”.

So what could be more fitting than for these great institutions of personal development, and learning for the sake of learning, to become bastions of emotional education – equipping young people for the inevitable challenges they will face as they embark on the journey to full financial, emotional and intellectual independence?

And, as the number of young people pursuing higher education globally continues to rise, don’t these institutions also have a responsibility, as well as the potential, to build a brighter future for society on all levels: academically, economically and emotionally?

A once-prestigious subject vilified by modern elites

Philosopher Alain de Botton, in his book ‘The School of Life’, argues that emotional education, which for two thousand years stood as the pinnacle of literary and intellectual achievement, “has been vilified by [modern] elite culture”.

Its decline, he argues, is in part due to the modern university system, where an obsession with facts and accuracy took over. And yet it remains “at once deeply relevant and widely neglected”.

“The challenge before us,” says Botton, “is to break down emotional intelligence into … a curriculum of emotional skills. We should be ready to embark on a systematic educational programme in an area that has for too long, unfairly and painfully, seemed like a realm of intuition and luck.”

He goes on: “We live in a culture that refuses to foreground the idea of lifelong emotional development, not because such a script is inherently impossible, but because it hasn’t taken the care to write it.”

Who better to take the helm and rewrite the lives of future generations than the modern universities of today?

[“source=forbes”]