Why does Sainsbury’s want to buy Argos?

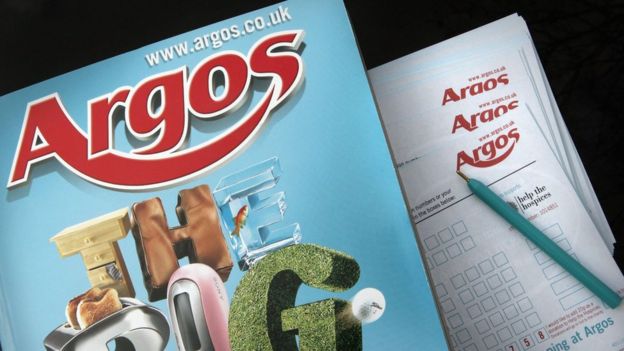

“The laminated book of dreams,” was how comedian Bill Bailey once jokingly described the plastic-coated Argos catalogue.

Yet for supermarket chain Sainsbury’s could it actually prove true?

Its original declaration of interest in Argos and Homebase owner Home Retail Group stunned the City, with many retail experts and investors questioning the logic of such a deal.

But Sainsbury’s, which has already been trialling Argos concessions in 10 of its stores, has now offered £1.3bn to win control of Home Retail Group.

It argues buying the group would help it to boost sales growth, improve its delivery networks, and mean they could sell their products to each other’s customers.

The supermarket says the leases of around half of Argos’ 734 stores across the UK are due for renewal over the next four to five years, and it is believed to have identified between 150 and 200 stores which it could shut and move into a nearby Sainsbury’s store.

Image copyrightGetty Images

Image copyrightGetty ImagesBut analysts have suggested the greatest prize of all could be Argos’ delivery network. The chain may be best known for its hefty, encyclopedia-like catalogues – the basis of many a child’s Christmas wishlist – but it has been steadily replacing the ring-bound catalogues and iconic blue pens with iPad-style terminals.

‘Amazon with stores’

The shift is part of Argos’ mission announced in late-2012 to reinvent itself as “a digital retail leader”.

Order something from Argos before 6pm and you can have it by 10pm that same day any day of the week, for £3.95.

It’s basically an “Amazon with stores” as investment bank Morgan Stanley puts it.

Image copyrightThinkstock

Image copyrightThinkstockJames Walton, chief economist at food and grocery research charity IGD, says for that reason Sainsbury’s move may just make sense because it will help it to fulfil the “I want it now” demand from shoppers, what he calls “the fast order fulfilment service aspect of online”.

“It was one of those announcements that you thought afterwards ‘of course that’s going to happen’,” he says.

“It’s all about serving the customer where they want it, when they want. Shopping your way anyway without any compromise. It’s a huge logistical challenge which raises the bar as far as shoppers are concerned,” he says.

Yet online supermarket shopping is a vastly different world from normal online shopping for say clothes or books.

For a start hardly anyone does it. Online purchases currently account for just 5% of UK grocery sales, according to IGD.

This partly comes from low demand: people don’t like to pay delivery fees, the delivery slots are often inconvenient and the food isn’t always fresh.

Image copyrightOcado/Newscast

Image copyrightOcado/NewscastMeanwhile, the problem for supermarkets is most online transactions aren’t profitable.

Setting up a technology platform and an initial distribution network can cost tens of millions of pounds. Online only supermarket Ocado is a case in point, it took 15 years to make its first annual profit.

On top of this, the supermarket then has all the extra costs of picking the food, packaging it and delivering it. Food items require different temperatures and items are often fragile or bulky making the process more difficult and costly.

Analysts estimate that while supermarkets typically charge just £3 or £4 for each home delivery, the actual cost to them is £20, meaning they are effectively paying customers to shop online with them.

Image copyrightSean Gallup

Image copyrightSean GallupYet long term it could prove worthwhile. Accountancy firm PwC says its researchshows that shoppers who do start online grocery shopping, increased the amount they spent with that retailer.

“This leads us to believe that if a retailer could solve the profitability challenge, and persuade more people to adopt a multichannel grocery shopping approach, the additional sales volume could propel growth significantly,” it says.

‘Huge threat’

Long term Amazon may force all of the big four supermarkets – Sainsbury’s, Asda, Tesco and Morrisons – to invest further in online delivery. The online giant’s recent launch of Pantry in the UK – a next-day delivery service which charges by the box and is available to its £79-a-year Prime members – suggests it has the big four in its sights.

The service currently only offers household essentials, which are not fragile and therefore more cost effective to pick and deliver, but is believed by many analysts to be a forerunner to the launch of a full grocery service including fresh products, which it already offers in some parts of the US.

Amazon could eventually be a “huge threat,” says The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Chief Retail & Consumer Goods analyst, Jon Copestake.

“It’s not a threat to groceries at this stage. But its proposition is evolving in a way that makes it difficult for retailers to break up. It offers a whole host of differentiated products – such as Amazon TV, next-day delivery etc rolled into one package that it’s quite difficult to break into.

“It’s difficult for retailers to counter as they have a much much more simplified offer,” he says.

Image copyrightGetty Images

Image copyrightGetty ImagesAs supermarkets well-documented, drawn-out price war with each other, but principally against the discounters which have been stealing their customers with alarming speed, gradually eliminates the cost differences between the big four supermarkets, delivery networks could be the thing that helps to differentiate them.

“Grocery retail is locked into a price war that doesn’t show any sign of ending. The supermarkets are struggling with margins and closing their largest stores.

“Supply chain and logistics might protect their margins. It’s a fightback of one kind,” adds Mr Copestake.

Yet independent retail veteran Richard Hyman is sceptical and believes Sainsbury’s and its rivals would be better off focusing their attention on their core business: food.

“However unexciting and old fashioned it may seem it’s the products that matter. The delivery system is a support act.

“There’s no uniqueness there. No customer is going to buy a delivery system. It’s what is being delivered which is the key. You’ve got to make sure it’s the optimum quality and optimum price,” he says.

[Source:- BBC]